- Home

- Tania Malik

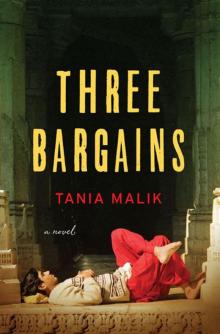

Three Bargains: A Novel Page 10

Three Bargains: A Novel Read online

Page 10

Madan contemplated turning back and confronting the pandit. But it would elicit the same lecture from Avtaar Singh. He’s only an old pandit, set in his thoughts and ways, Avtaar Singh would say. What can he do to you? You’re the one who is young; you need to control your temper.

He saw that Pandit Bansi Lal was at Avtaar Singh’s side, conversing rapidly, and for now it seemed best to go ahead and join the men outside.

He left a message for Jaggu to meet him later at home, and they all piled into the car and headed for Dawn Guesthouse. Earlier that day, Jaggu seemed excited about something. “Wait until tonight,” he had told Madan, when Madan caught him whispering with Feroze.

Now Feroze was sitting next to him, humming, and when he caught Madan looking at him he said, “So you’re meeting Jaggu tonight?”

“Yes, that’s the plan,” said Madan.

Feroze laughed and Madan noticed Gopal and Harish grinning as well. “What? What’s going on tonight?”

“Nothing, nothing,” said Feroze, refusing to meet Madan’s eye and smiling all the while.

Dhiru Sood was finishing a cup of tea in the front lawn of the guesthouse. When Madan and the boys entered, he looked up curiously from his newspaper, and it was not until they were standing before him that comprehension dawned on the young fellow.

He stood up with a start, and reached down as if to touch his toes. It was then that Madan noticed the small boy playing by his father’s feet. Dhiru Sood picked up his son and turned toward the house. On the front steps a girl in a red frock played with some dolls. Dhiru Sood ushered the boy up the stairs and shouted to someone to take the children and lock the door. Witnessing the flurried activity brought on by their presence, a mixture of anger and weariness overcame Madan. Dhiru Sood’s father must have enlightened his son about the consequences of pursuing the ownership of their land and to the dangers that awaited him in Gorapur. And here was Dhiru Sood bringing his whole family along like they were going on holiday somewhere.

“So many people for me?” Dhiru Sood said. There was a time to be sarcastic, but Madan wasn’t sure for Dhiru Sood’s sake if this was the time.

“Get in the car,” said Feroze.

“Why don’t we talk here?” Dhiru Sood asked. But they pushed him out through the gate to the waiting car.

Dhiru Sood tried to hold back a tremble and look friendly when they shoved him into the middle of a storage shed made of hastily erected brick walls and a tin roof in the middle of some placid fields. Sacks of grain piled in high mounds at the entrance hid them from prying eyes. They had debated where to take Dhiru Sood, but their favorite spot on the canal was too far and no one wanted to drive back to the factory, so the shed ended up being their chosen spot.

“Boys, you have to understand. I have the title papers; the law is on my side. This is not done,” Dhiru Sood said, his tremble sabotaging his show of bluster. “Let’s go home, and I will not tell anyone about this.” He folded his hands, asking for clemency. “This is just a misunderstanding.”

“What about the going to the commissioner’s office? Ha? Just a misunderstanding, ha?” Feroze said, punching Dhiru Sood on the side of his head.

“Please, I have small children,” Dhiru Sood pleaded. “I don’t want any trouble. I am happy to reimburse Avtaar Singh for the land. Please tell him I am ready to offer him anything he needs. In fact, why don’t you take me to him and I’ll tell him myself?”

Madan had had enough of this man. If Dhiru Sood knew that Avtaar Singh would come after him, then why had he gone forward? Wasting everyone’s time with unnecessary meetings and actions. And why did they always mention their children? Like having children was a defense against bad judgment.

He popped Dhiru Sood right in the mouth and the men cheered because not only did it shut him up but two teeth fell to the floor. Someone punched him in the gut and Dhiru Sood tried to talk again but went limp, collapsing to the floor. They began to kick him, rocking Dhiru Sood with the ferocity of their attack.

“Please . . .” begged Dhiru Sood.

“Let’s do this quickly,” Madan said. He wanted to be done and out with Jaggu. The men paused, their panting filling the shed, and looked to Madan. He knew they were waiting for him but he couldn’t lift his hand to ask for a knife or a gun. Under his heel, he could feel the beat of Dhiru Sood’s heart but all he could see was the small boy clinging to his legs, the braids of the little girl swinging in the air when her mother swept her up and away.

A racket at the entryway forced their attention to Gopal, who had dashed out to the car and returned with a big grin and a plastic bucket swinging in his hands. Something inside the bucket was slamming against its sides and emitting an alarming growl.

“Stand back,” Gopal said, placing the bucket down in line with Dhiru Sood, who was trying to rise but for the shaking of his legs and the agony of his beating. The bucket moved on the floor from the force of the crazed animal inside. Carefully, Gopal kicked the bucket to its side, aiming its mouth at Dhiru Sood. The lid fell off and out shot what looked to Madan like a large grayish yellow rat.

“Fucker,” said Feroze, raising his voice above the din, “where did you get a mongoose?”

Gopal pointed to the charging animal. “Look . . . it’s sick.” He tapped his own head and beamed at them.

At Gopal’s announcement, Madan and the other men hustled to the far end of the room, away from the rabid mongoose furiously racing in a straight line toward Dhiru Sood.

Dhiru Sood’s vision cleared and he managed to scoot a few inches back before the mongoose launched up and on him, and snapped at his shoulder. Letting out a bloodcurdling scream, he wrenched the creature off and scrambled to his feet, losing control of his bowels and filling the shed with a stomach-turning stench. Before Madan or the others could move, Dhiru Sood and the mongoose had escaped out the other end of the shed into the fields, one screaming, the other gnashing its teeth.

“Fuck,” said Gopal, “now what?”

Feroze was already at the doorway, taking aim. The screaming stopped right after the first shot, and the men applauded when in the dying light of the evening they saw Dhiru Sood stop and then crumple far in the fields.

“Should we go check?” said Feroze after a moment.

Gopal had thought to bring a mongoose but not a flashlight, and the men demurred, unwilling to venture out into the darkening fields where a rabid mongoose ran loose among the king cobras and Russell’s vipers.

Madan massaged his own shoulder, unable to comprehend the turn his thoughts were taking. From the arch of the doorway, he numbly watched and waited for any movement from Dhiru Sood, while inside his mind was on fire. Dhiru Sood’s boy had not wanted to let go of his father, blinking up at Madan as he hung on, his arms flapping in the air as he tried to reach out and maintain contact with his father’s leg when he was pulled away. It should take more than a blink of an eye, more than just one shot, to lose a father.

After making a show of his displeasure at Gopal’s antics, which had almost botched up their assignment for that evening, he gave a long-suffering sigh and, hoping the men would not think it too strange, said, “Let’s go. He’s not moving. If not now, then in five minutes he’ll surely be gone.”

The men were surprised but relieved. They were anxious to get on with their plans for the evening. “I’ll explain to Avtaar Singh if he asks,” Madan said, setting their minds to rest.

He had to stop himself from physically pushing the men back into the car, and willed them to drive fast back to the factory. A half hour later Madan was tearing back down the same road on a borrowed motorcycle, headed to the storage shed. His plan seemed possible and impossible at the same time. He gunned the throttle and cursed himself, cursed Dhiru Sood and swore at the men and their petty games, but was grateful for the distraction that had given Madan a way out. Feroze was a decent shot, but to shoot a running man in the waning light could have affected his aim. Madan hoped it was something else that had caused Dhiru S

ood to fall.

Collecting a couple of empty gunnysacks from the shed, he followed the straight line of the flashlight. Dhiru Sood had made a heroic attempt at escape from both the mongoose and the men, and had fallen many yards away from the shed. Madan used the flashlight to check his wounds. The bite didn’t seem too deep, but it was the animal’s saliva that could be just as dangerous. An injury on Dhiru Sood’s left side had clotted into a dried mass but seemed no more than a flesh wound. Still, it made Madan reassess his opinion of Feroze’s shooting skills.

Dhiru Sood let out a frightened squawk when he saw Madan leaning over him but Madan had no time to explain. Cautiously, so as to avoid contact with the possibly infected saliva or splattered blood, he wrapped Dhiru Sood in the large, rough gunnysacks and, leveraging his own weight, pulled Dhiru Sood up. He half dragged, half carried him back to the motorcycle while wishing he wouldn’t make so much noise but Dhiru Sood would not stop crying, moaning or gulping for air.

With Dhiru Sood up front and leaning against his chest, and the gunnysacks between them, Madan gunned the motorcycle all the way to Dr. Kidwai’s. The doctor was finishing up his dinner and he motioned Madan to his adjacent clinic, expressing surprise that Madan had brought a victim and not one of their own, as was usually the case. Covered in sweat and grime, and unable to understand his own actions, Madan contrived to tell the doctor about the bite and the shot. The efficient doctor knew not to ask too many questions and bandaged, medicated and dispatched Dhiru Sood with the first of his series of anti-rabies shots.

Dhiru Sood then managed to sit behind Madan on the motorcycle, breathing shallowly and groaning with every bump in the road. “You’re lucky this time,” said Madan, helping Dhiru Sood up the steps of the darkened guesthouse. “Why did you return to Gorapur? You should’ve known this would happen.”

“In my father’s time, yes,” wheezed Dhiru Sood. “But it’s a lot of land, worth a lot of money, and I hoped by now things would have changed.”

“Nothing changes here.” Madan was furious at the man’s naïveté. “This is not a big city like Bombay. Here there is only Avtaar Singh.” He placed Dhiru Sood gingerly on the guesthouse’s steps. “What do you do in Bombay?”

“I’ve a jewelry shop. Diamonds, mainly.”

“Even in Bombay that’s safer business than what you were planning here. Take your family and leave tonight. Don’t come back or it will end how it was meant to end today. Do you understand?”

Dhiru Sood nodded, and Madan turned to leave.

“Why did you come back for me?”

A dim, tentative light had come on inside the house. Madan could hear the slow creak of an opening door.

“For your children,” he said to Dhiru Sood.

The mosquitoes sizzled and fried to dust on the streetlights as Madan waited for Jaggu. Ma was busy at the main house and his grandfather cursed in his sleep beside him. Swati washed dishes by the hand pump. Madan watched as she pumped the water with one hand, rinsing each soapy plate with the other. The hem of her salwar’s long shirt was soaked.

What had he done? How had he done it? Even now, he couldn’t fathom the course of the day’s events. He walked up and down the courtyard, trying to control the spasms of fear ricocheting through him. If he mulled over his actions any longer, he would have to go over and finish Dhiru Sood right now.

“Are you going out tonight, Madan-bhaiya?” Swati asked.

She spoke softly and Madan had to strain to hear her, but this was how it was with Swati.

“Yes, with Jaggu.”

She had weaved the jasmine garland he had brought for her into her long braid and as she moved, a sweet whiff teased the air. He wondered why she had asked. Swati never went anywhere.

Her gait had something to do with her confinement. She hobbled as if walking on pins and needles, and could not go too far. “Give her time,” was the doctor’s advice when they had brought her home, “she is young.”

During her long recovery their room became a mini-hospital: medicines took over the spice shelf; balls of cotton, soaked through with disinfectant, filled up the garbage bins. Her body healed as best it could, otherwise it was as if an ax had come swinging down that day and silenced her forever. Night after night she lay huddled in the corner, wanting nothing, needing nothing, her fragmented gaze staring out into the room, wordlessly asking for what they could not give her.

She feared every footstep outside their door, keeping her head down or cowering when anyone happened to come by. For a while, she cut herself, small slits at the back of her legs as if she wanted to shift the pain from one part of her to another. Often Madan would awake to find her staring at him, like she was asleep with her eyes open.

Eventually it was Swati who began the task of putting her broken self back together. She started sitting outside with their grandfather, forced a word out here and there. Yet, as hard as she tried, it was as if one piece of the puzzle that was Swati always slipped away, floated beyond her grasp, leaving her, as she approached her teenage years, like a girl they were sure they knew, but could not recognize.

They tried sending her to school, thinking that being around other children might help. Madan had dropped her off at her class but was unable to find her at break time. She had wandered off, and Bittu-bhai, the paan-wallah, found her near his house, dirty and distraught. Their mother wouldn’t stop crying and when Madan questioned Swati, she said she had been feeling sleepy and went looking for her sleeping mat.

They tried school again, but it was no use—they would find her halfway home before the first bell rang. And so they left her where she was happiest, here in the servants’ quarters, singing to her dolls, taking care of their grandfather and helping at the main house.

“Girls do not need an education,” their mother said, comforting no one but herself.

Madan stepped out now and saw Jaggu turning the corner. He watched as Jaggu walked down the street, his spindly legs snapping ahead of him, his arms swinging to his shoulder and back down to his side, each step a frenetic dance.

No wonder he’s so thin, Madan thought, with all that constant activity.

Jaggu grinned when he saw Madan and Madan wondered what plans Jaggu had in store for them that night. Mostly they would go to the canal to drink or sometimes would watch a late-night show at Manika Cinema Hall. There was nothing Jaggu loved more than the movies.

“Whatever your problem,” he would explain to anyone who would listen, “you’re moody, you’re feeling sick, you have some misfortune, in the darkness there’s always an answer. Take my personal guarantee. There’ll be a song to lift your spirits or understand your despair. There’s always something beautiful to look at. It’s like drinking a strong medicine. It’ll take care of you, and make you forget where you hurt.”

Jaggu loved not only the dishum-dishum as the hero beat the villain to pulp but he also loved the romance, the beautiful dewy heroines wooed so perfectly through song and dance. He would exit each movie singing—the songs already part of his repertoire—and usually someone from the factory would see them and cuff him playfully behind the ear.

Tonight Madan was in no mood for the movies. He was glad to see a bottle peeking out from under Jaggu’s shirt. “Ready?” Jaggu asked.

“I’ve been ready for a long time,” said Madan, taking the bottle and tipping it to his mouth. “You got the good stuff today.” He flipped the bottle over to read the Presidents Premium whiskey label. Taking another swig, he passed the bottle to Jaggu, trying to hide the uncontrollable shaking of his hand. As much as he wanted to, he couldn’t tell Jaggu about what he had done. No one could know. He told Jaggu instead about Pandit Bansi Lal’s comments in the factory from earlier in the day.

“A man of God, but his dealings are more like the devil’s,” agreed Jaggu of the pandit.

The bottle was half empty before Madan realized they were heading away from the canal and the movie hall. “Where are we going?”

“You’ll see,” sa

id Jaggu. “It’s my early birthday present to you.”

“What? What’s all this going on? I just want to sit somewhere and finish this bottle.”

Madan peered at the name of the street. The darkness and the alcohol made it hard to read, and Jaggu was pulling him away, saying, “Don’t worry. This will be a night to remember, I tell you, come quick!”

Madan made out strains of music and laughter in the distance. They walked toward a house at the end of the street. “Here it is,” said Jaggu, peering at the number. “Come on, they’re expecting us.”

Madan was not sure he liked this feeling of suspense, but he wanted nothing more than to forget the doubt and dread pressing down on him. Jaggu pushed open the door and someone called out. Madan turned to see Feroze lying on the divan. A woman wearing only a petticoat and blouse, her untied hair spilling over her shoulders, sat on his lap and fed him sips from a tumbler.

“Oh, there is our hero!” Feroze got up and the woman fell to the side. He threw his arm around Madan’s shoulder.

“Champa, bitch, where are you?” Feroze bellowed. “Look what I’ve got for you today!”

From the adjoining room another woman came bustling in, a grease-stained apron over her salwar kameez. “Look,” said Feroze, pushing Madan and Jaggu forward. “Today we have some new and fresh members, Champa.” He tottered, leaning too close to her. “Only your best cunts will do. No overused maal.”

Champa ignored him and looked at the two boys. “That’s all right,” she said. “But no one gives for free.”

“We’ve got money,” said Jaggu, taking out a wad of notes from his pocket. Madan looked at him in surprise and Jaggu winked. “I’ve been saving up.”

Champa looked disinterestedly at the money and called a string of names. The girls poured out like ants from an anthill, pushing and shoving each other. Beside him, Madan heard Jaggu make a short noise, like a yelp.

Three Bargains: A Novel

Three Bargains: A Novel