- Home

- Tania Malik

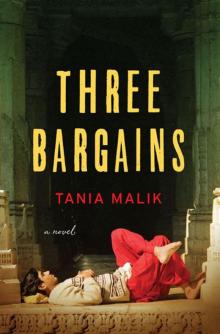

Three Bargains: A Novel Page 15

Three Bargains: A Novel Read online

Page 15

CHAPTER 11

THEIR LONG BRISTLY TAILS WAVING LIKE FLAGS, THE MONKEYS screeched and showered Madan with leaves as he walked down the brick path to the temple. He had no offerings they could pilfer off him as they did to unsuspecting worshippers, stealing fruit and sweets brought to pacify or beg the gods. Anyway, he wasn’t here for any of those reasons. He was here to pick up Pandit Bansi Lal. Today was Avtaar Singh’s birthday and, as always, the day started with a havan, the massive prayer ceremony that Minnu memsaab orchestrated on this day every year.

Before ascending the grand marble staircase leading to the main temple floor, he removed his shoes, placing them in one of the compartments in the shelves outside the temple, safe from the greedy monkeys. He walked around the main cupola, barely glancing at the statues of Ram and Sita with their hands raised in blessing, and went around to Pandit Bansi Lal’s private quarters.

Silagaon Temple, much like Gorapur Academy, was another consequence of Avtaar Singh’s philanthropic excesses. He financed its domes and spires of pink sandstone, its latticed marble columns, and its idols covered with flakes of gold. He’d procured the land on which the temple stood, paying off various government beauraucrats to acquire the property belonging to the state government. In the matters of the Almighty, Avtaar Singh did not hold back.

Madan met one of Pandit Bansi Lal’s assistants, who led him to the pandit’s rooms.

Pandit Bansi Lal sat on his charpai holding court, a few of his pujaris in chairs and on mats around him. Madan stood by the door as the assistant whispered in his ear about Madan’s arrival. Neither with a twitch of his eyebrow nor a turn of his head did Pandit Bansi Lal acknowledge Madan’s presence, talking on and on to the others in the room without interruption. This went on for over ten minutes before Madan walked out. The pandit knew he was here and where to find him. He wasn’t going to wait at the door like a browbeaten dog.

Sitting back in the car, he slammed the door shut harder than intended. It wasn’t really about Pandit Bansi Lal.

Two weeks had passed since their return from Mussoorie with no sign or sight of her, and every memory had become a deafening reverberation making each thought, each small action, a concentrated effort.

“What’s the matter with you lately?” asked Jaggu. He concluded that Madan’s unrest was due to his longing for college to start and though Jaggu was off the mark, the thought of college gave Madan an idea. He grasped on to the hope that she would be there at the havan today, and in some way he would be able to tell her of his plans.

From the corner of his eye he saw Pandit Bansi Lal approach the car and stand by the back passenger door. He knew the pandit was waiting for him to hop out and open the door. He didn’t move and Pandit Bansi Lal waited. Even Avtaar Singh would open his own door. Finally, after a few minutes Madan opened the door, only because he didn’t want the pandit to be late for Avtaar Singh’s havan.

Quiet at first, Pandit Bansi Lal uttered an, “Om,” drawing out the word till it was tight as a stretched elastic band. He began to recite the Hanuman Chalisa, his voice rising and falling as he chanted, “O God . . . fully aware of the deficiency of my intelligence, I concentrate my attention on Pavan Kumar and humbly ask for strength, intelligence and true knowledge to relieve me of all my blemishes . . .” He chanted on and on all the way to the house.

The driveway was noisy and crowded as if the market had relocated to the front of the house. Caterers, waiters and tent-wallahs careened and jostled into one another while carting their supplies back and forth. A large white marquee covered most of the front lawn, its canvas walls billowing in the gentle warm wind. Under the tent, white cotton sheets covered the grassy lawn, and red cushions lay scattered all around. On the fringes, pedestal fans whirred to and fro. At the head of all this, a square fire pit was being set up for the prayer ceremony and an overstuffed cushion was placed near it for Pandit Bansi Lal. Tables and chairs would replace all this when it was time for lunch.

Madan parked the car and once again Pandit Bansi Lal waited for him to open the door. As Pandit Bansi Lal lumbered up the stairs into the house, he said to no one in particular, “It would benefit some people to read the Hanuman Chalisa at least one hundred times in succession—they will attain much-needed peace of mind.” And he was in the house before Madan had a chance to say anything.

He went around to the kitchen, which was relatively quiet. All the cooking and preparations were taking place outside on the stone patio, where the caterers had set up makeshift stoves and tavas. Already simmering in the blackened vats and cauldrons were some of Avtaar Singh’s favorite vegetarian dishes, for there could be no chicken or meat served during a havan. He stopped to watch as someone stirred the sarson ka saag, the dark green mustard leaves releasing a fragrant aroma wafting as far as the servants’ compound.

Inside the kitchen, Swati prepared a large pot of tea, his mother giving instructions as she kneaded the dough. “Serve the tea,” she said to Swati, “and then give the girls their breakfast.”

A girl he recognized from his class at Gorapur Academy also helped in the kitchen today. He could not remember her name, but he knew her father, who worked at the factory.

“Can I get you anything, Madan-bhaiya?” asked Swati, when he stepped in.

“There’s no time for that!” said his mother, shooing Swati out with the tea tray. “Go, go, go! You know Pandit-ji can’t be kept waiting.”

Swati hurried out and he leaned against the counter. The girl smiled coyly up at him, her long braid swinging as she dried the dripping plates. Madan barely noticed. The world was spinning around him, yet inside he felt an impenetrable stillness. Butter sizzled and melted around the parantha on the tava, and his mother wiped her hands on the towel, giving the smiling girl a stern look.

“So what can I get you? Eat something. Have you eaten yet?” his mother asked, frowning and peering closely at him. Today, even the customary terseness which had invaded the tone of her voice in any conversation with Madan since his father’s passing didn’t rankle.

Madan began to assure her he was fine, but she was on to her next task. He stepped out of the kitchen and ran into Bhola, Trilok-bhai’s driver. Was she already here and he was distracted by other useless things? He greeted Bhola and continued quickly on, pretending not to notice that the old driver wanted to talk. Out front, Jaggu called to him from the other side of the driveway. He was directing the arriving cars and drivers to the parking area on the far side of the house, out of sight of the guests.

Perfumed, well-dressed men and women filled the tent, chatting and finding places to sit. Ladies covered their heads with duppatas for the prayers, while men used white handkerchiefs. Pandit Bansi Lal sat near the fire pit with Avtaar Singh, who was in a raw-silk kurta of gold and taupe, and a bejeweled Minnu memsaab. It looked like Pandit Bansi Lal was about to begin. Madan searched frantically. He had a full view of the inside of the tent from his vantage point by the stairs.

He saw Trilok-bhai standing next to Neeta memsaab, his paunch almost obscuring his wife. Neha was not with them. Soon the throng began to settle and part, and then there she was. He hadn’t seen her in a salwar kameez before, and it took a moment for his gaze to settle on her. She turned, looking out of the tent to the front of the house, their eyes meeting across the sitting crowd. A blast from the fan whipped her hair into her face and as she brushed the strands away, she smiled at him, and Madan smiled back. Then Rimpy appeared, pulling Neha to where Dimpy and their other friends sat, and she followed Neha’s gaze to the front and to Madan. He turned at once and went to Jaggu, his only thought to see Neha alone.

As it turned out, it wasn’t hard. Once the prayers ended, he was at the front steps with Jaggu, who was talking about all the food they would get to eat that day, now at the house and later at the factory. On Avtaar Singh’s birthday all of Gorapur went to bed with full stomachs. The guests were rising and stretching, their legs cramped from sitting cross-legged for the past hour. They chatted

and waited for the caterers to set up lunch. Neha paused in front of them at the bottom of the stairs, her eyes flicking quickly to Jaggu.

“Hello,” she said, her tone formal, unsure.

Madan nodded and grinned, even though he knew he should appear indifferent.

“I am going inside, it’s so hot out here,” she said.

“Yes,” said Madan. “There are guest rooms through the corridor past the kitchen, just near the back.”

She nodded, and he followed her with his eyes until she went inside.

“These rich memsaabs can’t even take a bit of sun,” said Jaggu. “She was friendly, though, smiling at you like that.”

“She knows me from the Mussoorie trip,” he said, his mind racing ahead. “Listen, Jaggu, can you do me a favor?”

“What?”

“Just ask Avtaar Singh when Pandit Bansi Lal is ready to go. Then can you drive him back to the temple?”

“Why?” said Jaggu. Madan wished for once that Jaggu would just get on with things instead of asking so many questions.

“You know . . .” he said. “He was on my case again on the way here. I don’t want to be around him. It’s not good for my health.”

Jaggu laughed, understanding at once. “Okay, okay,” he said, but did not move.

Madan looked at Jaggu pointedly.

“Oh, you mean I ask now?” Jaggu said.

“Yes,” said Madan. “Pandit-ji will be the first to eat and the first to leave.”

He watched as Jaggu headed toward the tent, and then raced around to the back. The house would be empty except for a few elderly people who preferred sitting inside where it was cooler, and they would be in the main drawing room. He rushed through the kitchen, glad his mother wasn’t there. He hadn’t thought about what he would say if he ran into her. In the corridor, he saw Neha and called to her. She came running, he took her hand and they hurried back out of the kitchen. He did a quick look around. Only the caterers were there now, and they were busy, but anyone they knew could come up at any moment.

He was never so glad for the size of the house. There were plenty of nooks and corners to hide behind, and he knew them all. Still holding her hand, he led her away from the kitchen, around to the back, where the verandas opened out into the gardens. How many times had he and the twins played hide-and-seek back here? He’d taught them to make slingshots with the Y-shaped branch ends of the mango trees that now provided a spotty screen. He pulled her into a corner where the house’s wall joined a veranda.

Time had sweetened the taste of her lips, the tenderness of her touch. He felt compelled to run his hands over her again.

“Stop, stop,” she said finally. “Is that all we’re going to do?” She giggled into his neck.

“I can’t stop,” he said as she pushed him, playfully, but not enough to move him away.

“Listen,” he said into her hair. “Are you going to the same college with Rimpy and Dimpy?” The twins were going to the girls’ college in Gorapur.

She nodded. “Why?”

It came to him all of a sudden. She had to continue her education somewhere, and even Trilok-bhai would not be so paranoid as to have her tutored at home. Now that she was back under his roof, Trilok-bhai would assume she was under his control. That’s how men like Avtaar Singh and Trilok-bhai thought—in absolutes.

“We can meet when college starts,” he said. “We’ll have to figure out when you can get out. You used to do it at your old school.”

“Yes, but that was different,” she said, mulling over his idea. “But it’s not impossible. I’ll have to see how things work here.”

He’d already thought of that too. He knew the girls’ college. There was a guard in the front gate but that was not the only way in and out. All she need do was call him at the factory, whenever she got the phone to herself at home, and let him know what time she could get out the next day. He might get some good-natured ribbing if anyone perchance picked up his phone, but no one would know it was her. He would meet her outside, by the delivery gate.

She shivered. “Don’t worry,” he said. “It’ll work.”

“My father was furious the last time,” she said. “I was locked in my room for over a week and my mother had to beg him to let me come out to eat at the dining table. But . . .” She pulled his head down and he had his answer.

She looked past his shoulder to the end of the property. “What’s there?”

He knew without turning. It was the wall that separated the servants’ quarters. He wondered why she asked. She had the same area at her house.

“All lasting change begins with a revolution,” she said, dreamily staring past the high walls into the world beyond.

“And what big rebellion are you planning?” He playfully kissed her neck, breathing in her floral perfume.

“I’m not joking.” She leaned away from him. Her hands trailed up his arm. The activity at the front of the house faded to an indistinct buzz. “I feel like I can’t breathe,” she said.

“Sorry,” he said, trying to give her space, but she didn’t let him move away.

“No, that’s not what I meant.” Pushing a strand of hair behind her ear, she looked up at him, he thought with shyness or hesitation, but there was no hint of docility when she spoke. “There’s this town I heard about, in the south, in Kerela. It started as an experiment by a group of people. It’s a place where electricity never goes, and you can drink clean water out of the taps, and see the doctor for free, and everyone works together and lives peacefully.”

“Sounds like a paradise,” he said. “Though usually with these places there’s some guru or leader who seduces all the women and spends his followers’ money on a fleet of Rolls-Royces for himself.”

“There’s no leader in this town,” she said impatiently. “It has nothing to do with spirituality or religion or any hierarchy. Everyone is the same. There’s no place for ego or status. And you don’t work for yourself or your bank account. Your labor or skill is your contribution to the community, and the community looks after you.” She paused as if waiting to judge Madan’s reaction and then said, “It’s a place where we wouldn’t have to hide in a corner like this, and there are no walls separating you from anyone.”

He was unsure whether to take her seriously. “What are you saying? You want to leave Gorapur?” His mind reeled with the thought. He tried to kiss her again, to distract her. They had a few treasured moments and he did not want to spend it debating social reforms.

“I want to be with you, but is this it? Is this all we’ll ever have?” She didn’t make an effort to keep her voice low, letting it rise with her emotions. “Why do we keep our plans so small? If I can slip out of school, we can slip out of this miserable town. Why are we staying here? Bending to this one’s rules and that one’s command. I can’t go on like this. It’s our life. We should choose how we live. It’s a right we all deserve.”

He cupped her face in his hands and tilted her gaze up toward him. Her eyes were bright. There was a small furrow on her brow, a line of distress he could not smooth away with a joke or a kiss, and it made him sad. Already he was dreading the few moments from now when she would leave to return to her family.

“I always thought I’d find a way to get there myself. Find out where it is and disappear one day. Now we can go together. Think about it. No fear, Madan. No nonsense with things that do not matter to us,” she said.

He couldn’t admit it to her, but his thoughts had turned to Avtaar Singh. Madan had never needed or wanted an alternative to Gorapur before. “Go anywhere, but there’s no place like Gorapur,” Avtaar Singh always said, and Madan always agreed. Here, in the shadow of Avtaar Singh’s house, it suddenly seemed an empty declaration, an advertisement in the paper that promised one thing and delivered another.

“Try to get out of college first and we can talk more then,” he said. He needed time to think. What kind of man would he be in a world where there was no Avtaar Singh?

She smiled, and pulled him to her by the collar of his shirt, returning his kisses with a long one of her own.

“I’d better go back,” she said. “They’ll begin to wonder.”

“One more minute,” he whispered.

“Madan?” Jaggu’s voice rang out from behind the trees and they barely managed to jump apart as he turned the corner and stood before them.

They all stared at each other for a moment. In a flash Neha ran past Jaggu, but he hardly noticed. He was staring at Madan like a truck full of logs had rolled down on him.

“What?”

“Jaggu—”

“You’re going to get us all killed!” Jaggu didn’t blink. He stared at Madan, frozen in place.

“No, Jaggu, listen—”

But Jaggu held up his hand, halting Madan’s move toward him. Jaggu leaned against the wall, struggling for air.

“Are you crazy? What’s going on? You’ve gone crazy,” he said, his arms flailing like he was the one going mad.

“Calm down, Jaggu, listen to me.”

“Listen to you? He’s going to kill us . . . we’re fucking gone . . . we’re gone . . . they won’t even find a fingernail.”

“No one is going to kill you or . . . anyone,” Madan said, fear briefly igniting in his gut. “How did you know I was here?”

“One of the caterers. He said he saw you go back here with a girl. I thought he was joking. I was tempted to put my fist to his ear.” Jaggu shook his head, giving a small laugh that sounded more like the cry of someone choking on his own blood.

After a while he wrestled himself under control. He straightened up. “What are you thinking? Do you even know what you’re doing?”

“Listen, Jaggu, you don’t have to get involved. Go back and forget about all of this. For me,” Madan sighed, “it’s too late.”

Jaggu snorted disbelievingly, and turned like he was going to leave. He kicked the ground, shaking his head. Madan watched as he muttered to himself.

Three Bargains: A Novel

Three Bargains: A Novel